"I always though that it was a shame that, when they dug the Panama Canal, they didn't screen!"

Bob Kelly in Boulder on 01/29/2010, answering a question about whether a coastal Paleoindian settlement along the western coast of North America might have allowed people to cross into the Caribbean Sea using the isthmus of Panama.

Saturday, January 30, 2010

Friday, January 29, 2010

Mica Glantz - Neandertal Paleobiogeography Colloquium at UC Denver

Next Friday, February 5 2010 (2:30PM, in AD 200), the UC Denver Anthropology Department is hosting a colloquium by Dr. Mica Glantz on Neandertal paleobiogeography in Central Asia (here'a link to a 2007 interview on her work on John Hawks' blog). Details below.

***********************************

Neandertal paleobiogeography in Central Asia: Testing the validity of the Neandertal range

Prof. Mica Glantz

Department of Anthropology

Colorado State University

Abstract:

The present study is primarily concerned with outlining the possible biogeographical limits of the Neandertal range. Until recently, the site of Teshik-Tash Cave in Uzbekistan was considered the eastern outpost of European Neandertals. In 2007, the mtDNA sequence of one Okladnikov Cave hominin was found to be similar to that of the Teshik- Tash child. Okladnikov Cave in southern Siberia is roughly 15 degrees to the north and east of Teshik-Tash. The working hypothesis is that the geographical region due east of Okladnikov and Teshik-Tash Caves expresses biogeographical factors that significantly differ from the region due west of these Neandertal sites. If this hypothesis is upheld, then these factors may define the limits of the Neandertal range. Results indicate that the biogeography of the region and the existing archaeological and hominin fossil records contain no clear evidence of a delimitation of Neandertal territory and that of East Asian archaics.

When: Friday February 5, 2010 – 2:30PM

Where: Administration Building, Rm. 200, University of Colorado Denver

***********************************

Neandertal paleobiogeography in Central Asia: Testing the validity of the Neandertal range

Prof. Mica Glantz

Department of Anthropology

Colorado State University

Abstract:

The present study is primarily concerned with outlining the possible biogeographical limits of the Neandertal range. Until recently, the site of Teshik-Tash Cave in Uzbekistan was considered the eastern outpost of European Neandertals. In 2007, the mtDNA sequence of one Okladnikov Cave hominin was found to be similar to that of the Teshik- Tash child. Okladnikov Cave in southern Siberia is roughly 15 degrees to the north and east of Teshik-Tash. The working hypothesis is that the geographical region due east of Okladnikov and Teshik-Tash Caves expresses biogeographical factors that significantly differ from the region due west of these Neandertal sites. If this hypothesis is upheld, then these factors may define the limits of the Neandertal range. Results indicate that the biogeography of the region and the existing archaeological and hominin fossil records contain no clear evidence of a delimitation of Neandertal territory and that of East Asian archaics.

When: Friday February 5, 2010 – 2:30PM

Where: Administration Building, Rm. 200, University of Colorado Denver

Thursday, January 28, 2010

Housekeeping January 2010

I'll soon be doing a bit of housekeeping here at AVRPI. That will mainly entail cleaning the blogroll section to the right-hand side of the blog. As part of this mid-winter cleaning, I'll be removing dead links, and links to blogs that haven't been active in a while. Also, if you have an archaeo/paleo/anthro themed blog and you'd like to see it included in the blogroll, feel free to contact me or leave a comment here. And speaking of comments, the blog's been getting quite a bit of spam lately, which is why I will keep comment moderation on for the time being, even if this slightly slows down some of the stimulating discussion that's been going on in several threads, especially the prehistoric ballistics and the Paleolithic island colonization ones.

Labels:

blogging

Archaeology and jobs never seen in movies

Here's a humorous breakdown of the most common occupations held by the protagonists of most Hollywood movies. Having enlightened us about what jobs are usually seen in movies, the writers also provide a 'top ten' of jobs never seen in movies. And what clocks in at #10? You guessed it, archaeologist!

Actually, that's not completely true... The Royal Tenembaums had Anjelica Huston playing Etheline Tenenbaum, an archaeologist shown doing reasonably realistic archaeological things at a couple of points in the movie. Of course, Wes Anderson's mother was an archaeologist, so he may have had a slightly less "Indiana Jones-ized" view of what we do than most directors. Can you, kind reader, think of other realistic depictions of archaeologists in movies/TV shows?

Archaeologist of really tedious, perpetually unfruitful digs: Movies tend to distort the profession of archaeologist and make it seem more glamorous than it really is. Instead of a swashbuckler rescuing ancient treasures from snake-pits, we’d like to see an archaeologist who digs tediously for months on end to unearth, say, one shoe horn from the Bronze Age every 11 years. Again, in keeping with this cinema verite approach, the archaeologists should not be played by actors fulfilling the screen portion of their good looking pop idol contract, but rather the type of personal-care avoiding sloppy intellectual whose own ears are a few missed cleanings away from being dig-worthy.

Actually, that's not completely true... The Royal Tenembaums had Anjelica Huston playing Etheline Tenenbaum, an archaeologist shown doing reasonably realistic archaeological things at a couple of points in the movie. Of course, Wes Anderson's mother was an archaeologist, so he may have had a slightly less "Indiana Jones-ized" view of what we do than most directors. Can you, kind reader, think of other realistic depictions of archaeologists in movies/TV shows?

Labels:

archaeology,

humor,

movies

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

Four Stone Hearth #85: Cold Wind Edition

A cold wind's blowing into Denver, bringing with it clouds and the promise for snow in the morning... what better time to inch ever closer to the Four Stone Hearth to warm one's anthropological body and soul!

I mean, it probably won't get as cold as Stockholm during the Middle Ages (as described at Testimony of the Spade), or Sweden in the Bronze Age, no matter how sweet their hoards of metal goods, at least as described at Aardvarchaeology! And, hey, at least it's still further south than, say, Wyoming, where you can find very interesting patterns in the distribution of archaeological remains, courtesy of Matt at Neolithic Revolutions.

But still, I'm sure some bundling up will be in order and, of course, this will require appropriate clothing. So why not get yourself a good discussion of ancient pants, courtesy of Kris Hirst. Of course, pants alone won't do... you'll probably need some shoes as well and a post on prehistoric footwear (or reconstructions thereof) at Middle Savagery might be just what you need.

No matter how good your clothes, though you ultimately will need some kind of shelter. Maybe something like the Neanderthal structures at Abric Romani, as described earlier here at AVRPI? Or maybe something in a warmer clime, like the open-air Lower Paleolithic site of Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, in Israel, as summarized by Tim at Anthropology.net? Of course, why live in a rockshelter or campsite when you could live in a Roman-age city, like Iruña-Veleia, where debate rages over the potential forgery of some inscriptions, as discussed in depth by Maju at Lehrensuge.

All this talk about authenticity and urban settings might prompt you to engage in some deeper reflections about the nature of the city and the human-built environment. If so, what better place to start than this reflection on balancing progress and history prompted by some of the art at Penn Station in New York, brought to you by Krystal at Anthropology in Practice? And while pondering this and other probing questions of anthropological import, consider Afarensis' thought-provoking post on the place of Melville Herskovits in the history of American anthropology and his work on the history and anthropology of African American. And speaking of introspective reflections on the development of anthropology as a discipline, definitely take the time to read Steve Chrisomalis' fantastic discussion of linguistic anthropology's place in a four-field discipline, and the state of that ideal today.

Well, that does it for today... while a cold wind's not always a bad thing (especially as channeled by BRMC!), it's nonetheless time to go warm myself up for real and say goodbye until next time at the Four Stone Hearth, which Magnus will have burning strong at Testimony of the Spade!

I mean, it probably won't get as cold as Stockholm during the Middle Ages (as described at Testimony of the Spade), or Sweden in the Bronze Age, no matter how sweet their hoards of metal goods, at least as described at Aardvarchaeology! And, hey, at least it's still further south than, say, Wyoming, where you can find very interesting patterns in the distribution of archaeological remains, courtesy of Matt at Neolithic Revolutions.

But still, I'm sure some bundling up will be in order and, of course, this will require appropriate clothing. So why not get yourself a good discussion of ancient pants, courtesy of Kris Hirst. Of course, pants alone won't do... you'll probably need some shoes as well and a post on prehistoric footwear (or reconstructions thereof) at Middle Savagery might be just what you need.

No matter how good your clothes, though you ultimately will need some kind of shelter. Maybe something like the Neanderthal structures at Abric Romani, as described earlier here at AVRPI? Or maybe something in a warmer clime, like the open-air Lower Paleolithic site of Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, in Israel, as summarized by Tim at Anthropology.net? Of course, why live in a rockshelter or campsite when you could live in a Roman-age city, like Iruña-Veleia, where debate rages over the potential forgery of some inscriptions, as discussed in depth by Maju at Lehrensuge.

All this talk about authenticity and urban settings might prompt you to engage in some deeper reflections about the nature of the city and the human-built environment. If so, what better place to start than this reflection on balancing progress and history prompted by some of the art at Penn Station in New York, brought to you by Krystal at Anthropology in Practice? And while pondering this and other probing questions of anthropological import, consider Afarensis' thought-provoking post on the place of Melville Herskovits in the history of American anthropology and his work on the history and anthropology of African American. And speaking of introspective reflections on the development of anthropology as a discipline, definitely take the time to read Steve Chrisomalis' fantastic discussion of linguistic anthropology's place in a four-field discipline, and the state of that ideal today.

Well, that does it for today... while a cold wind's not always a bad thing (especially as channeled by BRMC!), it's nonetheless time to go warm myself up for real and say goodbye until next time at the Four Stone Hearth, which Magnus will have burning strong at Testimony of the Spade!

Labels:

Anthropology,

carnival,

Four Stone Hearth

Saturday, January 23, 2010

Paleolithic Mediterranean island living, part 2

There's been some good discussion spurred by my earlier post on the reports of potential Lower Paleolithic stone tools found on Crete (and John Hawks also brought some additional observations to the debate). I'll be posting a few more things about some of the issues raised by the Cretan evidence in the coming days, but as I was recently going through a recent volume on prehistoric human-environment interactions (Fisher et al. 2009), I came across some interesting tidbits in a paper by Alan Simmons (2009) , which seemed relevant to the topic at hand:

And

References

Broodbank, C. 2000. An Island Archaeology of the Early Cyclades. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Cherry, J. 1990. The first colonization of the Mediterranean islands.: A review of recent research. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 3: 145-221.

Cherry, J. 1992. Paleolithic Sardinians? Some questions of evidence and methods. In Sardinia in the Mediterranean: A Footprint in the Sea (R. Tykot and T. Andrew, eds.), pp. 29-39. Sheffield University Press, Oxford.

Fisher, C.T., J.B. Hill, and G.M. Feinman (eds.). 2009.The Archaeology of Environmental Change. Socionatural Legacies of Degradation and Resilience.. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Patton, M. 1996. Islands in Time: Island Sociogeography and Mediterranean Prehistory. Routledge, New York.

Simmons, A.H. 1999. Faunal Extinctions in and Island Setting: Pygmy Hippopotamus Hunters of Cyprus. Kluwer, New York.

Simmons, A.H. 2009. The earliest residents of Cyprus: Ecological pariahs of harmonious settlers? In The Archaeology of Environmental Change (C. Fisher, B. Hill and G. Feinman, eds.), pp. 177-191. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

The Mediterranean islands produced some of the most sophisticated ancient cultures in the world, and yet we know relatively little about their early prehistory. Explicit anthropological approaches to the processes and consequences of their colonization are relatively recent developments (Patton 1996). The traditional view is that the islands were late recipients of Neolithic colonists who imported complete Neolithic packages but left few material linkages to their homelands. (Simmons 2009: 177)

And

The first human visitors to Cyprus, as reflected by the Akrotiri phase that is well documented thus far only at Akrotiri Aetokremnos (Simmons 1999), were either a late Epipaleolithic (roughly Natufian equivalent) or early Pre-Pottery Neolithic occupation. Akrotiri Aetokremnos assumes considerable importance because for many years claims for pre-Neolithic human occupation of many of the Mediterranean islands, including Cyprus, generally were unsubstantiated. While there are Epipaleolithic occurrences on some Aegean islands, these are relatively late. Furthermore, these islands are in proximity to the mainland (Broodbank 2000: 110-117; Cherry 1990, 1992; Patton 1996:66-72; Simmons 1999:14-27). [Simmons 2009: 179]

References

Broodbank, C. 2000. An Island Archaeology of the Early Cyclades. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Cherry, J. 1990. The first colonization of the Mediterranean islands.: A review of recent research. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 3: 145-221.

Cherry, J. 1992. Paleolithic Sardinians? Some questions of evidence and methods. In Sardinia in the Mediterranean: A Footprint in the Sea (R. Tykot and T. Andrew, eds.), pp. 29-39. Sheffield University Press, Oxford.

Fisher, C.T., J.B. Hill, and G.M. Feinman (eds.). 2009.The Archaeology of Environmental Change. Socionatural Legacies of Degradation and Resilience.. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Patton, M. 1996. Islands in Time: Island Sociogeography and Mediterranean Prehistory. Routledge, New York.

Simmons, A.H. 1999. Faunal Extinctions in and Island Setting: Pygmy Hippopotamus Hunters of Cyprus. Kluwer, New York.

Simmons, A.H. 2009. The earliest residents of Cyprus: Ecological pariahs of harmonious settlers? In The Archaeology of Environmental Change (C. Fisher, B. Hill and G. Feinman, eds.), pp. 177-191. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Labels:

colonization,

Crete,

Cyprus,

islands,

Mediterranean,

Paleolithic

Friday, January 22, 2010

Looking for contributors

The upcoming Four Stone Hearth anthropology blog carnival will take place here, at A Very Remote Period Indeed on Wednesday February 27 2010. Fell free to get in touch with me if you would like to contribute any anthropology-themed posts for inclusion.

Labels:

Anthropology,

blogging,

carnival,

Four Stone Hearth

Neanderthal wooden structures, sleeping areas and group size at Abric Romaní

Well, what do you know... it looks as though Neanderthals in Mediterranean Spain were up to all sorts of interesting stuff ca. 55-50kya! Hot on the heels of the news that ornaments and coloring materials were found in Mousterian deposits at Cueva Anton and Cueva de los Aviones,  we get news that Neanderthals at Abric Romaní (Spain, near Barcelona) appear to have had well defined sleeping areas that bear striking resemblance to those found in rockshelters used by extant hunter-gatherers (Vallverdú et al. 2010). But wait, there's more! The evidence reported by Vallverdú et al. (2010) also includes the impression of a ca. 5m-long worked wooden post (see image below) likely used as part of some kind of ephemeral wooden structure like a lean-to or a hut/tent pole. And as if that wasn't enough, an analysis of the hearths and occupied area suggests that level N (dated to ca. 55kya by U series) formed as the result of repeated occupations by small groups of 8-10 hominids who used the for brief periods of time, one of the first empirically derived for Neanderthal group size.

we get news that Neanderthals at Abric Romaní (Spain, near Barcelona) appear to have had well defined sleeping areas that bear striking resemblance to those found in rockshelters used by extant hunter-gatherers (Vallverdú et al. 2010). But wait, there's more! The evidence reported by Vallverdú et al. (2010) also includes the impression of a ca. 5m-long worked wooden post (see image below) likely used as part of some kind of ephemeral wooden structure like a lean-to or a hut/tent pole. And as if that wasn't enough, an analysis of the hearths and occupied area suggests that level N (dated to ca. 55kya by U series) formed as the result of repeated occupations by small groups of 8-10 hominids who used the for brief periods of time, one of the first empirically derived for Neanderthal group size.

There's a lot to digest in that preliminary report. First, the sleeping areas. This is important since it relates to the structured use of space, which is often argued to be something that differentiates modern humans from Neanderthals. Of course, the recent paper on Lower Paleolithic spatial organization at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov in Israel has done a lot to dispel that preconception lately, but it's still framing how many researchers conceptualize Neanderthals. The Romaní investigators identified 19 hearths in Level N (you can see them as the dark patches in the picture above), and identified that they were arranged in three distinct areas within the rockshelter: inner (closest to the backwall), frontal (around the largest travertine accumulations), and frontal (in the center of the shelter). An analysis of the hearths indicates that they were used repeatedly in a smouldering manner for brief periods of time. As well, the distance between the hearth and the distance between the hearths and the backwall in the inner zone all combine to "suggest that this space represents a sleeping-and-resting area in the Romaní record (Vallverdú et al. 2010:142). As the authors emphasize, there is a small but growing number of studies that have documented similar types of spatial organization at other Middle Paleolithic sites, including notably Tor Faraj, Jordan (Henry et al. 2004). These all suggest that Neanderthals were able to segregate their activities as well as to use the thermal characteristics of shallow hearths and rockshelter morphology to create comfortable sleeping areas, including at sites like Abric Romaní that faces N/NE and would not have mostly shaded and humid without such effective accommodations.

The wooden pole that the authors describe was identified on the basis of its impression in travertine deposits (see part b of the picture above which also shows what appears to be the pattern created by bark on the impression). "The travertine wood imprint measures 510cm in length and 6cm in width at one end and 3cm at the other. It has a rectilinear form, an absence of branches, and it ir fragmented, indicating probably that this piece of wood was subject to human modifications" (Vallverdú et al. 2010:140). Its position at the edge of the inner zone which is where evidence for a sleeping area was identified suggest to the authors that it was part of some sort of larger structure, maybe "a simple triangular structure leaning against the wall' (Vallverdú et al. 2010:143). Here, I'll simply point out that there is evidence for wooden structures at other Middle Paleolithic (and by extension Neanderthal) sites in Europe, including notably at the site of La Folie, France (which I discussed at length in another post), and which dates to ca. 57.2kya, roughly the same age as Level N at Abric Romaní.

The aspect of the paper which I thought was especially thought-provoking concerns the estimation of Neanderthal group size. Based on the size of the inner zone, the authors "assume that a density of individuals using 1.5-2m2 each or a group of 8-10 hominids could occupy this area. Hearth spacing in sleeping areas [based on ethnographic examples - JRS] suggests an occupation number of 4-6 individuals." (Vallverdú et al. 2010:143). While this estimate is extremely interesting in light of what it may tell us about Neanderthal social organization, before people go out and use this paper to show that Neanderthals lived in extremely small groups, it is important to emphasize that this group size is characteristic of fleeting occupations of the site. If anything, this may be telling us something about the size of task group (or some similar social unit) more than anything about overall group size in Neanderthals. If Level N at Romaní reflects a satellite site to a larger 'home base' type settlement, then we may start extrapolating from that 8-10 person figure some more grounded estimates of the extent of Neanderthal social units broadly speaking. Fascinating.

References

Henry, D. O., H. J. Hietala, A. M. Rosen, Y. E. Demidenko, V. I. Usik and T. L. Armagan. 2004. Human Behavioral Organization in the Middle Paleolithic: Were Neanderthals Different? American Anthropologist 106:17-31.

Vallverdú, J., Vaquero, M., Cáceres, I., Allué, E., Rosell, J., Saladié, P., Chacón, G., Ollé, A., Canals, A., Sala, R., Courty, M., & Carbonell, E. (2010). Sleeping Activity Area within the Site Structure of Archaic Human Groups Current Anthropology, 51 (1), 137-145 DOI: 10.1086/649499

There's a lot to digest in that preliminary report. First, the sleeping areas. This is important since it relates to the structured use of space, which is often argued to be something that differentiates modern humans from Neanderthals. Of course, the recent paper on Lower Paleolithic spatial organization at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov in Israel has done a lot to dispel that preconception lately, but it's still framing how many researchers conceptualize Neanderthals. The Romaní investigators identified 19 hearths in Level N (you can see them as the dark patches in the picture above), and identified that they were arranged in three distinct areas within the rockshelter: inner (closest to the backwall), frontal (around the largest travertine accumulations), and frontal (in the center of the shelter). An analysis of the hearths indicates that they were used repeatedly in a smouldering manner for brief periods of time. As well, the distance between the hearth and the distance between the hearths and the backwall in the inner zone all combine to "suggest that this space represents a sleeping-and-resting area in the Romaní record (Vallverdú et al. 2010:142). As the authors emphasize, there is a small but growing number of studies that have documented similar types of spatial organization at other Middle Paleolithic sites, including notably Tor Faraj, Jordan (Henry et al. 2004). These all suggest that Neanderthals were able to segregate their activities as well as to use the thermal characteristics of shallow hearths and rockshelter morphology to create comfortable sleeping areas, including at sites like Abric Romaní that faces N/NE and would not have mostly shaded and humid without such effective accommodations.

The wooden pole that the authors describe was identified on the basis of its impression in travertine deposits (see part b of the picture above which also shows what appears to be the pattern created by bark on the impression). "The travertine wood imprint measures 510cm in length and 6cm in width at one end and 3cm at the other. It has a rectilinear form, an absence of branches, and it ir fragmented, indicating probably that this piece of wood was subject to human modifications" (Vallverdú et al. 2010:140). Its position at the edge of the inner zone which is where evidence for a sleeping area was identified suggest to the authors that it was part of some sort of larger structure, maybe "a simple triangular structure leaning against the wall' (Vallverdú et al. 2010:143). Here, I'll simply point out that there is evidence for wooden structures at other Middle Paleolithic (and by extension Neanderthal) sites in Europe, including notably at the site of La Folie, France (which I discussed at length in another post), and which dates to ca. 57.2kya, roughly the same age as Level N at Abric Romaní.

The aspect of the paper which I thought was especially thought-provoking concerns the estimation of Neanderthal group size. Based on the size of the inner zone, the authors "assume that a density of individuals using 1.5-2m2 each or a group of 8-10 hominids could occupy this area. Hearth spacing in sleeping areas [based on ethnographic examples - JRS] suggests an occupation number of 4-6 individuals." (Vallverdú et al. 2010:143). While this estimate is extremely interesting in light of what it may tell us about Neanderthal social organization, before people go out and use this paper to show that Neanderthals lived in extremely small groups, it is important to emphasize that this group size is characteristic of fleeting occupations of the site. If anything, this may be telling us something about the size of task group (or some similar social unit) more than anything about overall group size in Neanderthals. If Level N at Romaní reflects a satellite site to a larger 'home base' type settlement, then we may start extrapolating from that 8-10 person figure some more grounded estimates of the extent of Neanderthal social units broadly speaking. Fascinating.

References

Henry, D. O., H. J. Hietala, A. M. Rosen, Y. E. Demidenko, V. I. Usik and T. L. Armagan. 2004. Human Behavioral Organization in the Middle Paleolithic: Were Neanderthals Different? American Anthropologist 106:17-31.

Vallverdú, J., Vaquero, M., Cáceres, I., Allué, E., Rosell, J., Saladié, P., Chacón, G., Ollé, A., Canals, A., Sala, R., Courty, M., & Carbonell, E. (2010). Sleeping Activity Area within the Site Structure of Archaic Human Groups Current Anthropology, 51 (1), 137-145 DOI: 10.1086/649499

Labels:

hearths,

Middle Paleolithic,

Mousterian,

neanderthals,

spatial organization,

structure,

wood

Thursday, January 21, 2010

Hunter-gatherer higher education

I recently discussed the call for paleoecologists and ecologists should make explicit effort to integrate their results and interpretations, and how Paleolithic archaeologists and anthropologists working with hunter-gatherers can, in a way, be considered as having made good strides in a similar direction. Since that post, I've been reflecting about my own training (received and given, since I teach a hunter-gatherer class every other year), and I realized that all the coursework I ever took on foragers was taught by archaeologists (Jim Savelle at McGill, Curtis Marean at ASU), which made me wonder if we can really speak of such good integration between the subfields of anthropology when it comes to foragers.

With that in mind, I figured I'd do a little informal polling of my readership to see whether my experience is normal or an aberration (in the nicest sense of the word, of course!). So, if you're an anthropologist, what kind of anthropologist did you get your hunter-gatherer education from? Feel free to add any comment if the options below are too constraining.

With that in mind, I figured I'd do a little informal polling of my readership to see whether my experience is normal or an aberration (in the nicest sense of the word, of course!). So, if you're an anthropologist, what kind of anthropologist did you get your hunter-gatherer education from? Feel free to add any comment if the options below are too constraining.

Labels:

Anthropology,

education,

hunter-gatherers,

university

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

AIA Denver Lecture - Linda Scott Cummings

The Denver Chapter of the Archaeological Institute of America is hosting a lecture by Dr. Linda Scott Cummings of the PaleoResearch Institute, Inc. this coming Sunday, January 24. It will take place at the Tattered Cover bookstore downtown, at 2:00PM. Details below.

“Delving into the Mystery of the Visible, Nearly Visible, and Invisible Records of PaleoEnvironment and PaleoSubsistence at Archaeological Sites"

Linda Scott Cummings, PhD

Tattered Cover Bookstore (1668 16th Street, Denver, CO), 2:00PM

Understanding the environmental setting in which people have lived is critical to understanding any people. So, too, does our picture of diet color our opinion of people of the past? Both combine to build a picture of the past as “real people” who lived in well-defined time and space.

“Delving into the Mystery of the Visible, Nearly Visible, and Invisible Records of PaleoEnvironment and PaleoSubsistence at Archaeological Sites"

Linda Scott Cummings, PhD

Tattered Cover Bookstore (1668 16th Street, Denver, CO), 2:00PM

Understanding the environmental setting in which people have lived is critical to understanding any people. So, too, does our picture of diet color our opinion of people of the past? Both combine to build a picture of the past as “real people” who lived in well-defined time and space.

Labels:

AIA,

Denver,

diet,

paleoecology,

public lecture

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

Prehistory according to La Linea

One of my favorite shows growing up was La Linea ("The Line"), of which we would see short clips as intermissions between children's shows on TV in . La Linea is the brainchild of Italian cartoonist Osvaldo Cavandoli, who created a whole series of these segments in which this benignly irate line-drawn character (hence the name) and who speaks in Milanese-inflected gibberish gets into sundry trouble and comical situations. As it turns out, there is an episode of La Linea that illustrates how the character would fare in prehistoric times... let's just say stone tool technology is not his forte!

Labels:

humor,

La Linea,

prehistory,

TV

Monday, January 18, 2010

Very low human population size in the Lower Pleistocene

From the NY Times, reporting on a study estimating the "effective" population size of hominins ca. 1.2 million years ago based on three versions of the human genome:

That notion that humans were not very successful is an interesting one, especially considering how far-ranging they were by that point. By that tims, hominins were found all over Africa, all the way to Indonesia, along the northern Mediterranean rim and even as far septentrionally as the Republic of Georgia (i.e., the Dmanisi specimens). I'll be curious to see how the study accounts for this, unless this is it:

Can't wait to read the paper.

They put the number at 18,500 people, but this refers only to breeding individuals, the “effective” population. The actual population would have been about three times as large, or 55,500.

Comparable estimates for other primates then are 21,000 for chimpanzees and 25,000 for gorillas. In biological terms, it seems, humans were not a very successful species, and the strategy of investing in larger brains than those of their fellow apes had not yet produced any big payoff. Human population numbers did not reach high levels until after the advent of agriculture.

That notion that humans were not very successful is an interesting one, especially considering how far-ranging they were by that point. By that tims, hominins were found all over Africa, all the way to Indonesia, along the northern Mediterranean rim and even as far septentrionally as the Republic of Georgia (i.e., the Dmanisi specimens). I'll be curious to see how the study accounts for this, unless this is it:

But that estimate would apply to the worldwide population only if there were inbreeding between the humans on the different continents. If not, and if modern humans are descended from just one of these populations, like Homo ergaster in Africa, then the estimate would apply only to that.

Richard G. Klein, a paleoanthropologist at Stanford, said it was hard to believe the population from which modern humans are descended was as small as 18,500 “unless they were geographically restricted to Africa or a small part of it.”

Can't wait to read the paper.

Labels:

genetics,

human evolution,

human expansion,

population size

Early modern human parietal art at Fumane Cave

http://www.grottadifumane.it/FOTOGALLERY-DELLA-GROTTA.html

The issue with these fragment has been to precisely determine how old they are, since they are in secondary position, that is to say, they were not found where they were painted. It seems that during a cold snap following the moment on which the designs were painted on the cave, the vault surface spalled off and the fragments fell on deposits that were, logically, more recent than the paintings themselves. The oldest fragment (Fragment I in the figure below) bears a representation of some kind of quadruped was recovered in Unit A2, which is the base of the Aurignacian deposits at the site, whereas Fragment II ("the shaman", so called because the anthropomorphic figure it bears also shows some horn-like features) was recovered from the a pile mound of stones located at the cave's mouth, while the other decorated blocks were recovered in later (i.e., more recent) Aurignacian and Gravettian layers. In Italy, the Gravettian is securely attributed to modern humans, who are also widely thought to be the makers of the Aurignacian, and its earliest expression, the Protoaurignacian.

The five decorated vault fragments from Grotta di Fumane.

From: Broglio et al. (2009:756, Plate 2).

From: Broglio et al. (2009:756, Plate 2).

The main issue, chronologically speaking, has been to determine when the figures were painted on the cave vault, since the layers in which they were recovered only provide a terminus ante quem for their age, in other words, an upper limit for their age. So, at first glance, there is no evidence for the age of these paintings beyond that of the layers in which they were recovered. However, in this study, Broglio et al. (2009) make the case that all the paintings date to the earliest Aurignacian at the site, that is to level A2. Historically, the dating of the earliest Aurignacian at Fumane has been hotly debated, but the authors present new dates for previously dated charcoal samples that have undergone, for the new dates, a new, more thorough pretreatment (i.e., ABOx SC). This has provided two statistically equivalent age determinations of 35,640 +/- 220 and 35,180 +/- 220 BP for level A2. Interestingly, and fittingly in light of my recent post on the presentation of calibrated and uncalibrated radiocarbon dates, they conclude that, by reference to the calibration curve based on the Cariaco Basin data and the GISP2 Greenland ice core, that "the chronological data show that Protoaurignacian Unit A2 dates to between 43,250 to 40,500 BPGISP2, with an age of 41,000BPGISP2 being statistically more likely" (Broglio et al. 2009:760; my translation, emphasis added).

What allows them to tie the paintings to that age determination is the study of ochre found in Unit A2. The base and top of that layer include conspicuous concentrations of red ochre, and some ochre crayons were also recovered from A2. The clincher is that these crayons are made of the same ochre as that which was used for the parietal art. This is demonstrated by a brief compositional analysis of the pigments using various methods, that also indicates that these ochres are circum-local in provenience, being found in the Lessini Mountains, at the southern edge of which Fumane sits.

In sum, while the decorated pieces themselves were not dated directly, this study provides some strong circumstancial evidence for their being of early Aurignacian age. If this attribution is correct, it provides us with some solid data about some of the iconographic canons and artistic techniques used by early Aurignacian foragers in northern Italy and some insights into the variability in artistic behavior within this cultural tradition at the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic.

update (01/18/2009: 12:20PM): Image of the paintings is now fixed.

References

Broglio, A., and G. Dalmieri (eds.). 2005. Pitture paleolitiche nelle Prealpi venete: Grotta di Fumane e Riparo Dalmieri. Memorie del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Verona, 2 serie. Sezione Scienze dell'Uomo. Verona, Italy.

Broglio, A., De Stefani, M., Gurioli, F., Pallecchi, P., Giachi, G., Higham, T., & Brock, F. (2009). L’art aurignacien dans la décoration de la Grotte de Fumane L'Anthropologie, 113 (5), 753-761 DOI: 10.1016/j.anthro.2009.09.016

Friday, January 15, 2010

Bob Kelly archaeology lectures at CU Boulder

Robert L. Kelly, a professor of archaeology in the department of anthropology at the University of Wyoming and a leading figure in research on prehistoric hunter-gatherers and the Paleoindian is giving the Distinguished Archaeology Lecture in the CU Boulder department of anthropology at the end of this month. He's also well known for his book "The Foraging Spectrum: Diversity in Hunter-Gatherer Lifeways" which is something of a must for anyone interested in hunter-gatherer adaptations, both in archaeology and as documented ethnographically. He'll be giving two lectures, both of which should be of interest to anyone interested in prehistoric foragers, the settlement of the New World and how archaeology can help understand some dimensions of human nature. Click on the flyer above for details about the lectures and info on how to get to them.

Labels:

archaeology,

Bob Kelly,

hunter-gatherers,

New World,

Paleoindian,

Robert Kelly

Prehistoric ballistics, or Mythbusters meets archaeology

Nicole Waguespack and a bunch of others (including four of the Mythbusters gang, which leads one to wonder whether this will be the basis of a future episode) ask the question: "Given that so many hunter-gatherers use/d stone-tipped projectile, what are the advantages of a stone tip relative to one whose point is simply sharpened wood?"

This is a good question to ask, since crafting an projectile point from stone consumes more time, effort and resources than simply sharpening the end of the shaft that you'll be making anyway. Hell, one could even argue that knapping a stone point incurs some additional risk since you risk slicing up your hand as you do so, as anyone who's ever tried their hand (eh!) at flintknapping knows all too well. These costs are all the more important to keep in mind given the frequency at which stone points break during use (Waguespack et al. 2009:787).

This is a good question to ask, since crafting an projectile point from stone consumes more time, effort and resources than simply sharpening the end of the shaft that you'll be making anyway. Hell, one could even argue that knapping a stone point incurs some additional risk since you risk slicing up your hand as you do so, as anyone who's ever tried their hand (eh!) at flintknapping knows all too well. These costs are all the more important to keep in mind given the frequency at which stone points break during use (Waguespack et al. 2009:787).

As the authors argue, it's generally assumed that stone makes for a more effective projectile point, though this has rarely, if ever, been tested empirically. As they state:

To test whether stone is actually more efficient, Waguespack et al. (2009) (available as a free pdf here)made replicas of six wooden and six stone-tipped arrows and shot them at a human torso-shaped block of ballistic gel, draping it with caribou hide in some cases to simulate the arrow having to pierce the thick skin of some animals. They conducted two tests. The first, designed to see whether stone and wood tips penetrate a target more or less deeply, had the arrows shot from a compound bow 1.1m away from the target. The second, designed to see if the two types of arrowheads have different degrees of accuracy, had the arrows shot from the same contraption but at a distance of ca. 16.75m.

The results of these experiments indicate that both arrow types bestow equal degrees of precision to their users and, most importantly, that stone-tipped arrows provide only marginally higher degrees of target penetration (about 10% more), especially considering that both arrow types penetrated more than 20cm into the target. These observations lead the authors to conclude that the benefits of using stone-tipped arrows probably do not make up for the extra time, resources and risk involved in making them. Therefore, they argue, it is likely that the ubiquity of stone tips is driven by some other consideration, either other parameter of hunting effectiveness or social dimensions of projectile point making, such as the prestige derived from skillful stone working.

While there is some ethnographic evidence for the functional argument (e.g., Ellis 1997), Waguespack et al. (2009) provide a good discussion of why stone points are effective conveyors of social identities and/or a form of costly signaling. Costly signaling basically refers to behaviors that are not strictly functional but nonetheless serve to augment the social standing of the people able to effectively engage in them, be it through more finely honed skills or access to resources unavailable to others (or their profligate use).

Currently having lithics on the brain since I'm preparing to teach my Lithic Analysis seminar this coming terms (there's still some open seats if you're an interested student living in Colorado!), I thought this was a really good study that yields both interesting results and a powerful demonstration of how experimental archaeology can help answer long-standing anthropological questions (and, in this case, in a manner appealing to a wide audience!). With that in mind, I was nonetheless left wondering whether results might have differed if other types of projectiles had been used (e.g., darts propelled using a spear thrower, or hand-cast spears or javelins). Likewise, I would have been really interested in seeing the penetration results of both point types in the accuracy experiment, since 16.75m (ca. 50 feet) is likely to have been a more appropriate prey-hunter distance approximation than 1.1m (ca. 4 feet) used in the penetration experiment.

In any case, if the authors are right, this opens up some really interesting avenues to research technologically-mediated costly signaling in the deep past. Since stone points were used as far back as the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age (ca. 300,000 years BP), it implies this practice may be quite old. In sum, this paper provides a good theoretical and empirical basis to ground studies of costly signaling as reflected in some classes of chipped stone implements (i.e., points) which are certainly better in that respect than handaxes, as I've discussed recently.

Update: Turns out this episode already aired a long time ago, on Feb. 13, 2008 to be precise. That's what I get for not having cable, let alone a TV!

References

Ellis, C.J. 1997. Factors influencing the use of stone projectile tips: an ethnographic perspective, in Projectile technology (H. Knecht, ed.), pp. 37-74. New York, Plenum Press.

Waguespack, N.M., Surovell, T.A., Denoyer, A., Dallow, A., Savage, A., Hyneman, J., & Tapster, D. (2009). Making a point: wood- versus stone-tipped projectiles Antiquity, 83: 786-800

As the authors argue, it's generally assumed that stone makes for a more effective projectile point, though this has rarely, if ever, been tested empirically. As they state:

"Numerous ‘common knowledge’ explanations appear to be generally accepted regarding the superiority of stone, and to a lesser extent, osseous point tips relative to sharpened staves (e.g. Guthrie 1983; Arndt & Newcomer 1986). Assumptions concerning performance (e.g. durability of the tip), lethality (e.g. length of cutting edge, depth of penetration) and aerodynamics (e.g. weight distribution, flight paths) abound. Unfortunately, few of these assumptions have been verified experimentally (Waguespack et al. 2009:787)."

To test whether stone is actually more efficient, Waguespack et al. (2009) (available as a free pdf here)made replicas of six wooden and six stone-tipped arrows and shot them at a human torso-shaped block of ballistic gel, draping it with caribou hide in some cases to simulate the arrow having to pierce the thick skin of some animals. They conducted two tests. The first, designed to see whether stone and wood tips penetrate a target more or less deeply, had the arrows shot from a compound bow 1.1m away from the target. The second, designed to see if the two types of arrowheads have different degrees of accuracy, had the arrows shot from the same contraption but at a distance of ca. 16.75m.

(from Waguespack et al. 2009: Figure3, p. 794.)

The results of these experiments indicate that both arrow types bestow equal degrees of precision to their users and, most importantly, that stone-tipped arrows provide only marginally higher degrees of target penetration (about 10% more), especially considering that both arrow types penetrated more than 20cm into the target. These observations lead the authors to conclude that the benefits of using stone-tipped arrows probably do not make up for the extra time, resources and risk involved in making them. Therefore, they argue, it is likely that the ubiquity of stone tips is driven by some other consideration, either other parameter of hunting effectiveness or social dimensions of projectile point making, such as the prestige derived from skillful stone working.

While there is some ethnographic evidence for the functional argument (e.g., Ellis 1997), Waguespack et al. (2009) provide a good discussion of why stone points are effective conveyors of social identities and/or a form of costly signaling. Costly signaling basically refers to behaviors that are not strictly functional but nonetheless serve to augment the social standing of the people able to effectively engage in them, be it through more finely honed skills or access to resources unavailable to others (or their profligate use).

Currently having lithics on the brain since I'm preparing to teach my Lithic Analysis seminar this coming terms (there's still some open seats if you're an interested student living in Colorado!), I thought this was a really good study that yields both interesting results and a powerful demonstration of how experimental archaeology can help answer long-standing anthropological questions (and, in this case, in a manner appealing to a wide audience!). With that in mind, I was nonetheless left wondering whether results might have differed if other types of projectiles had been used (e.g., darts propelled using a spear thrower, or hand-cast spears or javelins). Likewise, I would have been really interested in seeing the penetration results of both point types in the accuracy experiment, since 16.75m (ca. 50 feet) is likely to have been a more appropriate prey-hunter distance approximation than 1.1m (ca. 4 feet) used in the penetration experiment.

In any case, if the authors are right, this opens up some really interesting avenues to research technologically-mediated costly signaling in the deep past. Since stone points were used as far back as the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age (ca. 300,000 years BP), it implies this practice may be quite old. In sum, this paper provides a good theoretical and empirical basis to ground studies of costly signaling as reflected in some classes of chipped stone implements (i.e., points) which are certainly better in that respect than handaxes, as I've discussed recently.

Update: Turns out this episode already aired a long time ago, on Feb. 13, 2008 to be precise. That's what I get for not having cable, let alone a TV!

References

Ellis, C.J. 1997. Factors influencing the use of stone projectile tips: an ethnographic perspective, in Projectile technology (H. Knecht, ed.), pp. 37-74. New York, Plenum Press.

Waguespack, N.M., Surovell, T.A., Denoyer, A., Dallow, A., Savage, A., Hyneman, J., & Tapster, D. (2009). Making a point: wood- versus stone-tipped projectiles Antiquity, 83: 786-800

Thursday, January 14, 2010

Yikes!!

Over the past few weeks, many friends and colleagues have sent me a link to this article by Thomas H. Benton who makes a good case about why most students planning to do so should in reality not go to grad school. If you're an undergraduate or returning student thinking about going for a PhD, especially in an overcrowded field like anthropology, you should definitely read it, as well as its companion piece on the need for current PhD students to think about unconventional ways of succeeding with a doctorate.

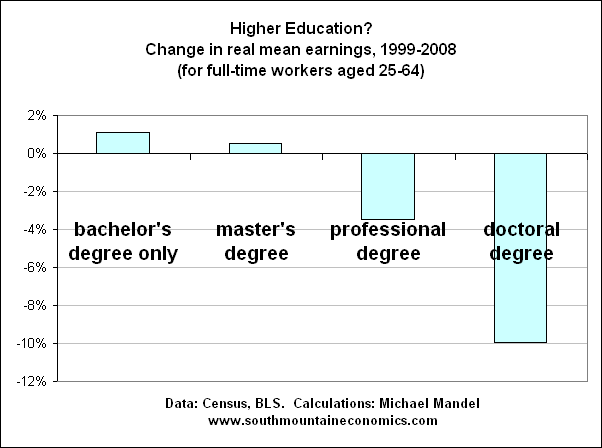

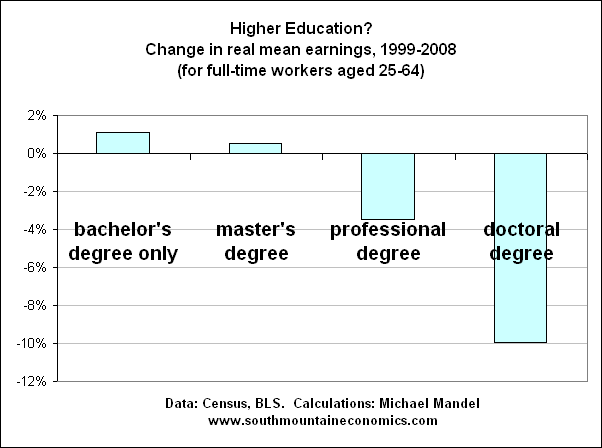

If you need additional information on why getting a PhD might not be such a great idea unless you're willing to sacrifice a good chunk of time for little reward, consider this figure published last week in a piece by Mike Mandel:

Out of all people with post-secondary degrees, the mean earnings of those holding a doctorate have fallen the most dramatically (ca. 10%) from 1999 to 2008! Now, maybe those with a PhD make more money to than a BA-educated worker to begin with (although whether that's the case in academia could certainly be debated), so that they still make a more comfortable living. Nonetheless, that's a pretty significant drop in the standard of living of PhD-holders, one that certainly should make one wonder about whether or not the return on your time and money investment in going for that PhD will be worth it in the end.

On an aside, I wonder whether or not this includes adjuncts or lecturers that are not the tenure-track but nonetheless qualify as full time workers based on the number of courses they teach. If so, this could certainly help explain part of the trend. Nonetheless, that this trend in post-PhD employment is having such an impact on the figures as a whole should serve as an additional bucket of ice water to be doused on students eager to pursue a PhD!

If you need additional information on why getting a PhD might not be such a great idea unless you're willing to sacrifice a good chunk of time for little reward, consider this figure published last week in a piece by Mike Mandel:

Out of all people with post-secondary degrees, the mean earnings of those holding a doctorate have fallen the most dramatically (ca. 10%) from 1999 to 2008! Now, maybe those with a PhD make more money to than a BA-educated worker to begin with (although whether that's the case in academia could certainly be debated), so that they still make a more comfortable living. Nonetheless, that's a pretty significant drop in the standard of living of PhD-holders, one that certainly should make one wonder about whether or not the return on your time and money investment in going for that PhD will be worth it in the end.

On an aside, I wonder whether or not this includes adjuncts or lecturers that are not the tenure-track but nonetheless qualify as full time workers based on the number of courses they teach. If so, this could certainly help explain part of the trend. Nonetheless, that this trend in post-PhD employment is having such an impact on the figures as a whole should serve as an additional bucket of ice water to be doused on students eager to pursue a PhD!

Labels:

academia,

earnings,

graduate school,

PhD

Paleolithic radiocarbon legerdemain

Two fundamental but often underappreciated aspects of radiocarbon dating concern the ages it yields and the fact that these ages need to be calibrated in order to get an age that can be expressed in calendar years. I say these aspects are underappreciated because of the way radiocarbon age determinations are usually reported in news reports and, more rarely, in actual research papers.

First, age determinations. Radiocarbon dating is based on the observation that given 14C in previously living organisms decays at a constant, predictable rate. In this case, half of a sample's 14C decays in about 5730 years in exponential fashion. This means, that after 5730 years, 1/2 of the 14C of a previously living organism remain, 1/4 remains after 11,460 years, etc. The uncertainty or error range reported for all radiocarbon dates is due to imprecision in counting the radioactive decay of carbon atoms in a sample, and it is a critical component of the date. What the error range indicates is a 66% chance that the age of a sample falls within the interval it brackets. Double the error range, and the resulting interval is 95% likely to include it. What is important to note is that raw radiocarbon age ranges are centered on the date that is statistically most likely to be the correct one for a dated sample. In that sense, it is somewhat warranted to use the date as a shorthand to discuss how old a sample is. That is, for a bone point dated to 13,400 +/- 100BP (these dates are expressed as before present, with the present assumed to be 1950), it is technically OK to say that it is a 13,400 year-old point, since that age is the most likely to be correct within the interval defined by the error range.

The problem, however, is that radiocarbon years don't correspond to calendar years, and usually underestimate the true age range of any given sample. This is because the concentration of atmospheric radiocarbon has not been constant over time. However, this problem can be corrected through the use of calibration curves based on the radiocarbon dating of samples of known age and extrapolated from the discrepancy between the two ages. Samples whose calendar age can be determined include historical artifacts, as well as organic remains that grow or accumulate in yearly increments, such as trees (that accumulated a new grwoth ring yearly) or corals.

Until recently, reliable calibration curves only stretched back to ca. 24,000 years BP, but recent developments have extended the range of calibration curves past 40,000 years BP, although some debate remains about some of the finer details of these more extensive curves. Regardless, from the perspective of paleoanthropology and especially that research focused on the timing of the disappearance of the Neanderthals, this has been a real boon, since it allows researchers to finally discuss this process in the chronology of the rest of recent human prehistory. For the transition interval (i.e., the period 30-40ky BP), the discrepancy between radiocarbon and calendar ages has been argued to be on the order of 5000 years, meaning that a radiocarbon date of, say 35,000 BP translates into a calendar (or calibrated) age of about 40,000BP.

This precision is good, but in my view, it's been abused somewhat on two levels. First, people wanting to emphasize how old a given object or associated assemblage is now systematically use calibrated ages. The reverse, however, is not true and the age of unexpectedly recent finds such as the late-lasting Mousterian assemblages of Gibraltar routinely continue to be presented in radiocarbon ages (i.e., ca. 28,000 BP, as opposed to say 32-33,000 cal. BP). I supposed this practice makes sense from a PR perspective, but it certainly muddles arguments about prehistoric chronology, especially for that (large) segment of the public that doesn't understand the subtleties of radiocarbon dating. It also creates a gap between earlier research that published radiocarbon ages and current papers that use calibrated ages or, worse, a combination of both.

The second problem is that most researchers and science journalists continue yo present and discuss calibrated ages in terms of their central tendencies when this is absolutely unwarranted. This is due to the fact that calibration curves are based on irregularities in atmospheric radiocarbon concentrations at various times in the past. This means that the smooth curve centered on a given age that is obtained by radiocarbon dating turns into a curve often best described as a hair-raising rollercoaster. Here's an example from the OxCal web site to illustrate what I mean:

This means that while the calibrated range corresponds to that of the original radiocarbon date, the mid-point of that range is not necessary the most likely one. This therefore means that, unlike for raw radiocarbon dates, it is often unwarranted to use the midpoint of a calibrated radiocarbon age range as shorthand for the most likely calibrated age of that sample.

I've simplified this discussion some for the sake of clarity (and kept it reference-free for the same reason), but it should now be clear why it really grinds my gears to see calibrated ages tossed around uncritically in the literature and, especially, in newsreports that discussed recent research that has an important chronometric dimension to it.

First, age determinations. Radiocarbon dating is based on the observation that given 14C in previously living organisms decays at a constant, predictable rate. In this case, half of a sample's 14C decays in about 5730 years in exponential fashion. This means, that after 5730 years, 1/2 of the 14C of a previously living organism remain, 1/4 remains after 11,460 years, etc. The uncertainty or error range reported for all radiocarbon dates is due to imprecision in counting the radioactive decay of carbon atoms in a sample, and it is a critical component of the date. What the error range indicates is a 66% chance that the age of a sample falls within the interval it brackets. Double the error range, and the resulting interval is 95% likely to include it. What is important to note is that raw radiocarbon age ranges are centered on the date that is statistically most likely to be the correct one for a dated sample. In that sense, it is somewhat warranted to use the date as a shorthand to discuss how old a sample is. That is, for a bone point dated to 13,400 +/- 100BP (these dates are expressed as before present, with the present assumed to be 1950), it is technically OK to say that it is a 13,400 year-old point, since that age is the most likely to be correct within the interval defined by the error range.

The problem, however, is that radiocarbon years don't correspond to calendar years, and usually underestimate the true age range of any given sample. This is because the concentration of atmospheric radiocarbon has not been constant over time. However, this problem can be corrected through the use of calibration curves based on the radiocarbon dating of samples of known age and extrapolated from the discrepancy between the two ages. Samples whose calendar age can be determined include historical artifacts, as well as organic remains that grow or accumulate in yearly increments, such as trees (that accumulated a new grwoth ring yearly) or corals.

Until recently, reliable calibration curves only stretched back to ca. 24,000 years BP, but recent developments have extended the range of calibration curves past 40,000 years BP, although some debate remains about some of the finer details of these more extensive curves. Regardless, from the perspective of paleoanthropology and especially that research focused on the timing of the disappearance of the Neanderthals, this has been a real boon, since it allows researchers to finally discuss this process in the chronology of the rest of recent human prehistory. For the transition interval (i.e., the period 30-40ky BP), the discrepancy between radiocarbon and calendar ages has been argued to be on the order of 5000 years, meaning that a radiocarbon date of, say 35,000 BP translates into a calendar (or calibrated) age of about 40,000BP.

This precision is good, but in my view, it's been abused somewhat on two levels. First, people wanting to emphasize how old a given object or associated assemblage is now systematically use calibrated ages. The reverse, however, is not true and the age of unexpectedly recent finds such as the late-lasting Mousterian assemblages of Gibraltar routinely continue to be presented in radiocarbon ages (i.e., ca. 28,000 BP, as opposed to say 32-33,000 cal. BP). I supposed this practice makes sense from a PR perspective, but it certainly muddles arguments about prehistoric chronology, especially for that (large) segment of the public that doesn't understand the subtleties of radiocarbon dating. It also creates a gap between earlier research that published radiocarbon ages and current papers that use calibrated ages or, worse, a combination of both.

The second problem is that most researchers and science journalists continue yo present and discuss calibrated ages in terms of their central tendencies when this is absolutely unwarranted. This is due to the fact that calibration curves are based on irregularities in atmospheric radiocarbon concentrations at various times in the past. This means that the smooth curve centered on a given age that is obtained by radiocarbon dating turns into a curve often best described as a hair-raising rollercoaster. Here's an example from the OxCal web site to illustrate what I mean:

This plot shows how the radiocarbon measurement 3000+-30BP would be calibrated. The left-hand axis shows radiocarbon concentration expressed in years `before present' and the bottom axis shows calendar years (derived from the tree ring data). The pair of blue curves show the radiocarbon measurements on the tree rings (plus and minus one standard deviation) and the red curve on the left indicates the radiocarbon concentration in the sample. The grey histogram shows possible ages for the sample (the higher the histogram the more likely that age is).

This means that while the calibrated range corresponds to that of the original radiocarbon date, the mid-point of that range is not necessary the most likely one. This therefore means that, unlike for raw radiocarbon dates, it is often unwarranted to use the midpoint of a calibrated radiocarbon age range as shorthand for the most likely calibrated age of that sample.

I've simplified this discussion some for the sake of clarity (and kept it reference-free for the same reason), but it should now be clear why it really grinds my gears to see calibrated ages tossed around uncritically in the literature and, especially, in newsreports that discussed recent research that has an important chronometric dimension to it.

Labels:

calibration,

dating,

legerdemain,

Paleolithic,

radiocabon dating

Wednesday, January 13, 2010

Lower-Middle Paleolithic island living?

There's a lengthy report describing some preliminary findings of Middle and perhaps even Lower Paleolithic artifacts on the Greek island of Crete that Thomas Strasser presented earlier this week. The report stresses especially that "ancient Homo species — perhaps Homo erectus — had used rafts or other seagoing vessels to cross from northern Africa to Europe via at least some of the larger islands in between."

If they're correct, Strasser's interpretations agree exactly with the results of work reported by Mortensen (2008) and which I already discussed a couple of years ago. Specifically, Mortensen argued that the implements he discovered "suggest that the first humans reached the island across the sea from Libya. That an early contact between northern Africa and southern Europe existed already during the Palaeolithic periods is a hypothesis now supported by most scholars."

Archaeoblog is skeptical about the findings, especially since no illustrations are provided that would help assess how 'Paleolithic' the implements look, while Hawks is also skeptical but suggests that fleeting human occupation may have occurred on Crete in the Middle Pleistocene as it may have on other large Mediterranean islands.

I'm of two minds about this. On the one hand, apparently large numbers of artifacts appear to have been found, on at least four distinct terraces as well as some rockshelters. Given that the team comprises a bona fide Paleoltihic archaeologist (C. Runnels), I see no reason to challenge the human-made nature of these implements. And, by referring to the Mortensen report, the current report certainly suggests that there was some sizeable human population on Crete at least during the Late Pleistocene (i.e., after ca. 130kya). That said, based on the description in the report, the stone tools in question appear to be handaxe-like things made on quartz (I recently discussed handaxes here). Quartz can be an impractical material to work, mainly because of its coarse crystalline structure, though in some cases, it can be fine-grained enought to yield decent knapped products. In other words, the structure of quartz often limits the range of formas that can be made from it, usually restricting them to relatively 'coarse' ones similar to some Lower Paleolithic types, which may account for some of the similarities mentioned in the text. Without some good illustration and photographs of these artifacts and of the quality of the quartz used to manufacture them, it's hard to make any kind of definitive statement.

Moving to the issue of the colonization of Crete, the whole 'they came straight from Africa' model is unconvincing to me. For one thing, the Greek mainland is much closer to the island than North Africa, and lower sea levels during cold periods of the Pleistocene would have made Crete more visible and accessible from there than from, say, Lybia. For another, the amount of finds and their time-transgressive nature (that is, they were found on four terraces spanning at least 90,000 years) suggest that people permanently settled the island for long stretches of the Middle Paleolithic. Both of these observations argue for hominins arriving to the island purely by chance. The question is whether or not they reached through seafaring. If they came from Europe, complex seafaring is unlikely to have been critical, whereas if they came directly from Africa, it would have been essential.

In a recent post, I detailed how seafaring - as inferred from the colonization of islands - has been argued by some to represent evidence of 'modern human behavior' (Norton and Jin 2009). However, in that case, colonization through seafaring was demonstrated by the presence of foreign lithic raw materials at specific site. If I understand the report about the finds by Strasser's team, however, the raw material of the Cretan finds appears to be exclusively local. The report states that

This local provisioning of raw material, in my view, argues against colonization by seafaring to a degree. Reference to the stylistic similarities of the Cretan handaxes and those from Africa is, again in my view, a non-argument, since handaxes are very similar in morphology and technology pretty much throughout the Old World (McPherron 2000).

References

McPherron, S.P. 2000. Handaxes as a Measure of the Mental Capabilities of Early Hominids. Journal of Archaeological Science 27:655-663.

Mortensen, P. 2008. Lower to Middle Palaeolithic artefacts from Loutró on the south coast of Crete. Antiquity 82(317): http://www.antiquity.ac.uk/ProjGall/mortensen/index.html.

Norton, C.J., and J.J.H. Jin. 2009. The evolution of modern human behavior in East Asia: current perspectives. Evolutionary Anthropology 18:247-260.

If they're correct, Strasser's interpretations agree exactly with the results of work reported by Mortensen (2008) and which I already discussed a couple of years ago. Specifically, Mortensen argued that the implements he discovered "suggest that the first humans reached the island across the sea from Libya. That an early contact between northern Africa and southern Europe existed already during the Palaeolithic periods is a hypothesis now supported by most scholars."

Archaeoblog is skeptical about the findings, especially since no illustrations are provided that would help assess how 'Paleolithic' the implements look, while Hawks is also skeptical but suggests that fleeting human occupation may have occurred on Crete in the Middle Pleistocene as it may have on other large Mediterranean islands.

I'm of two minds about this. On the one hand, apparently large numbers of artifacts appear to have been found, on at least four distinct terraces as well as some rockshelters. Given that the team comprises a bona fide Paleoltihic archaeologist (C. Runnels), I see no reason to challenge the human-made nature of these implements. And, by referring to the Mortensen report, the current report certainly suggests that there was some sizeable human population on Crete at least during the Late Pleistocene (i.e., after ca. 130kya). That said, based on the description in the report, the stone tools in question appear to be handaxe-like things made on quartz (I recently discussed handaxes here). Quartz can be an impractical material to work, mainly because of its coarse crystalline structure, though in some cases, it can be fine-grained enought to yield decent knapped products. In other words, the structure of quartz often limits the range of formas that can be made from it, usually restricting them to relatively 'coarse' ones similar to some Lower Paleolithic types, which may account for some of the similarities mentioned in the text. Without some good illustration and photographs of these artifacts and of the quality of the quartz used to manufacture them, it's hard to make any kind of definitive statement.

Moving to the issue of the colonization of Crete, the whole 'they came straight from Africa' model is unconvincing to me. For one thing, the Greek mainland is much closer to the island than North Africa, and lower sea levels during cold periods of the Pleistocene would have made Crete more visible and accessible from there than from, say, Lybia. For another, the amount of finds and their time-transgressive nature (that is, they were found on four terraces spanning at least 90,000 years) suggest that people permanently settled the island for long stretches of the Middle Paleolithic. Both of these observations argue for hominins arriving to the island purely by chance. The question is whether or not they reached through seafaring. If they came from Europe, complex seafaring is unlikely to have been critical, whereas if they came directly from Africa, it would have been essential.

In a recent post, I detailed how seafaring - as inferred from the colonization of islands - has been argued by some to represent evidence of 'modern human behavior' (Norton and Jin 2009). However, in that case, colonization through seafaring was demonstrated by the presence of foreign lithic raw materials at specific site. If I understand the report about the finds by Strasser's team, however, the raw material of the Cretan finds appears to be exclusively local. The report states that

... hand axes found on Crete were made from local quartz but display a style typical of ancient African artifacts.

“Hominids adapted to whatever material was available on the island for tool making,” Strasser proposes. “There could be tools made from different types of stone in other parts of Crete.”

Strasser has conducted excavations on Crete for the past 20 years. He had been searching for relatively small implements that would have been made from chunks of chert no more than 11,000 years ago. But a current team member, archaeologist Curtis Runnels of Boston University, pointed out that Stone Age folk would likely have favored quartz for their larger implements. “Once we started looking for quartz tools, everything changed,” Strasser says.

This local provisioning of raw material, in my view, argues against colonization by seafaring to a degree. Reference to the stylistic similarities of the Cretan handaxes and those from Africa is, again in my view, a non-argument, since handaxes are very similar in morphology and technology pretty much throughout the Old World (McPherron 2000).

References

McPherron, S.P. 2000. Handaxes as a Measure of the Mental Capabilities of Early Hominids. Journal of Archaeological Science 27:655-663.

Mortensen, P. 2008. Lower to Middle Palaeolithic artefacts from Loutró on the south coast of Crete. Antiquity 82(317): http://www.antiquity.ac.uk/ProjGall/mortensen/index.html.

Norton, C.J., and J.J.H. Jin. 2009. The evolution of modern human behavior in East Asia: current perspectives. Evolutionary Anthropology 18:247-260.

Labels:

colonization,

Crete,

islands,

Lower Paleolithic,

Middle Paleolithic,

seafaring,

stone tools

Gratuitous geladas and four stone hearths

Who likes 'em? A Primate of Modern Aspect, that's who! Do yourself a favor and check out the 85th installment of the Four Stone Hearth over at APMA's blog and show him some anthro love. There's a good amount of posts realting to non-human primates this time around, which is a nice change, too.

Oh, and keep in mind that the next FSH will be taking right here at A Very Remote Period Indeed, so please send me links to any posts you'd like to see included by January 26. Happy anthro reading!

Oh, and keep in mind that the next FSH will be taking right here at A Very Remote Period Indeed, so please send me links to any posts you'd like to see included by January 26. Happy anthro reading!

Labels:

carnival,

Four Stone Hearth,

primates

Tuesday, January 12, 2010

Paleo knighthood

I'm not sure why so many people e-mailed me links to this story, but this is definitely pretty cool.

I can only hope they knighted him using a strangulated blade!

Professor Paul Mellars, the Professor of Prehistory and Human Evolution at the Department of Archaeology, received a knighthood for his services to scholarship. He described receiving the honour as a “total surprise”.

Professor Mellars is an expert on the evolution and behaviour of early humans, and has published a wide variety of research papers and books on aspects of early human society. His recent research focuses on how Neanderthal populations were gradually replaced by modern homo sapiens...

I can only hope they knighted him using a strangulated blade!

Colorful Neanderthals on the half shell

There’s been a lot of buzz about the new paper by Zilhão et al. (2010) on the use of pierced shells and pigments by Neanderthals at the sites of Cueva de los Aviones and Cueva Antón, in southern Spain some 50,000 years ago, so I thought I’d give a few comments about it here.

This is a very significant study in that it strengthens the conclusions of previous research that suggests that Neanderthals habitually used pigments (e.g., Soressi and d’Errico 2007, which I discussed here). Importantly, it also broadens the range of color of these pigments to include, beyond black, yellows, reds, and orange. This matters because of the contention by some (e.g., Watts 2002) that the red color of ochre has important symbolic connotations that black pigments couldn’t have (e.g., blood, life, menstruation, etc.), and that this is an important distinction between Neanderthal and ‘fully modern’ use of coloring. Credibly establishing the presence of a range of colorful pigments derived from external sources at both these sites (their mineral sources are at least 3-5km distant from either cave) is therefore a major contribution to our knowledge of Neanderthal behavior and some of its symbolic underpinnings.

It of major interest in this paper is the description of a fragmented horse metatarsal with a pointed tip that bears traces of orange pigment at Cueva de los Aviones. The authors argue that “this naturally pointed bone may have been used as a stiletto for the preparation or application of mineral dyes or as pin or awl to perforate soft materials (e.g., hides) that were themselves colored with such dyes.” The relevance of this observation is highlighted by the manganese ‘crayons’ that were found at the Mousterian site of Pech de l’Aze, France (Soressi and d’Errico 2007), since it establishes that Neanderthals were not only using pigments in a range of color, but also that they had a range of manners of applying it to surfaces. This strongly hints at Neanderthal pigment use being a flexible behavior that varied from context to context, in contrast to their oft-repeated characterization of people who knew how to do only a limited range of things but do them quite well (which was one of the recurrent sound bites in the Human Spark documentary recently shown on PBS and which I will discuss on this blog in coming days).

Of course, in this ornament-obsessed period of paleoanthropological research, much of the buzz the paper has been getting derives from the fact that pierced shells were also recovered from both sites, many of which bore pigments. Early shell ornaments and associated pigments, of course, have recently been in the news (and discussed on this blog) and the focus of much attention in helping identify behavioral modernity (e.g., d’Errico et al. 2009). The authors make a strong case for the pierced shells having been purposefully selected by humans as ornaments (even if it’s a bit hard to get a clear idea of the trends in other periods based on the graph in the supplementary info), even if some of the perforations appear natural, artfully pointing out the interpretive double-standard that is sometimes applied to evidence associated with Neanderthals as opposed to that associated with modern humans.